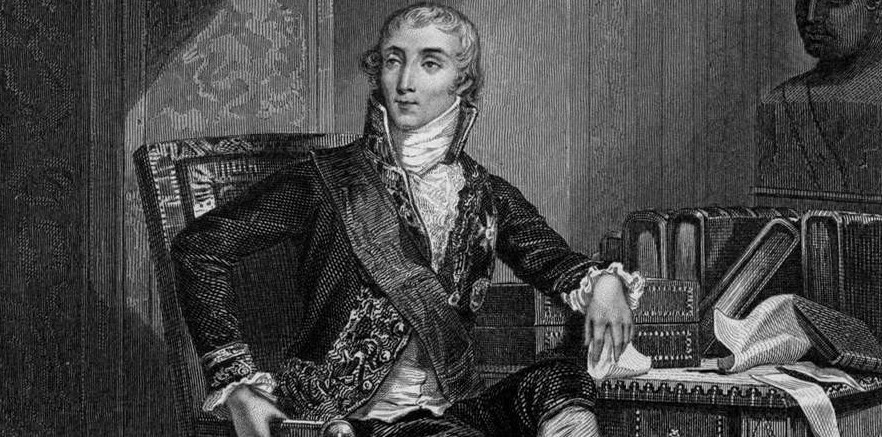

Joseph Fouché, a name synonymous with political cunning and unwavering survival, remains a fascinating and controversial figure in French history. From his early days as a revolutionary to his pivotal role in the Napoleonic era and beyond, Fouché’s life was a whirlwind of shifting allegiances, shrewd maneuvering, and an unparalleled ability to anticipate and control the currents of power. He was, arguably, the ultimate political survivor, a master of intrigue who navigated the turbulent waters of revolution and empire with remarkable skill.

Born in Nantes in 1759, Fouché initially pursued a career in the Church, studying at the Oratorian college. While he excelled academically, he lacked the charisma and social connections necessary for high ecclesiastical office. The French Revolution, however, presented him with an entirely new stage, one where his sharp intellect and pragmatic nature could truly shine.

As a representative to the National Convention, Fouché embraced radical republicanism, even voting for the execution of Louis XVI. He distinguished himself through his ruthless efficiency during missions to quell counter-revolutionary uprisings, most notably in Lyon, where he oversaw brutal purges. This period marked a defining moment, etching his name in the annals of French history as a figure of uncompromising action, even cruelty.

However, Fouché was no mere ideologue. He displayed a remarkable flexibility, understanding that survival in the ever-shifting political landscape required adaptability. He distanced himself from the excesses of the Terror, skillfully maneuvering to avoid falling victim to Robespierre’s purges and even contributing to the latter’s downfall. This marked the beginning of his ascent as a master political strategist.

His true calling, however, came with his appointment as Minister of Police under the Directory and later Napoleon Bonaparte. It was in this role that Fouché truly cemented his legend. He created a sprawling network of spies and informants, meticulously gathering information on everyone from the highest echelons of society to the common citizenry. He was a pioneer of modern surveillance, understanding the power of knowledge and leveraging it to maintain order and, more importantly, his own position.

Under Napoleon, Fouché’s influence grew. He was indispensable to the Emperor, providing him with vital intelligence and managing internal security. He skillfully thwarted conspiracies and maintained a semblance of stability amidst the constant warfare. However, he also acted as a check on Napoleon’s ambitions, often subtly influencing events and protecting his own interests.

Fouché’s ambition, however, proved to be his undoing. His penchant for playing both sides eventually led to his dismissal by Napoleon. Following the Bourbon Restoration, he even served as Minister of Police under Louis XVIII, a testament to his remarkable ability to reinvent himself and find a place in any regime. However, his past proved too much to overcome, and he was eventually exiled.

Joseph Fouché died in Trieste in 1820, a wealthy and disillusioned man. His legacy remains complex and debated. Was he a ruthless opportunist, a traitor willing to betray anyone for personal gain? Or was he a pragmatist, a necessary evil who used his skills to maintain order and prevent even greater chaos?

Ultimately, Joseph Fouché was a product of his time, a period of unprecedented upheaval and political volatility. He was a master of realpolitik, a survivor who understood the game of power and played it with unparalleled skill. He leaves behind a legacy of intrigue, a reminder that in the game of politics, knowledge is power, and adaptability is the key to survival. His life story serves as a cautionary tale and a fascinating study of ambition, betrayal, and the enduring quest for power in the face of revolutionary change.

The Serpent in the Garden: Stefan Zweig’s Portrait of Joseph Fouché

Stefan Zweig, master of the biographical miniature, possessed an uncanny ability to delve into the complexities of the human psyche. He sought out those figures whose lives were riddled with contradictions, individuals whose actions defied easy categorization. In his brilliant biography, Joseph Fouché, Zweig paints a chilling and compelling portrait of one of the most enigmatic and morally pliable figures of the French Revolution and Napoleonic era: Joseph Fouché, the Duke of Otranto.

Fouché, a man of immense intellect and even greater ambition, rose from relatively obscure origins to become one of the most powerful men in Europe. Zweig doesn’t shy away from portraying him as a ruthless pragmatist, a political shape-shifter capable of adapting to any regime, regardless of its ideology. He served under the Revolution, the Directory, Napoleon, and even the restored Bourbon monarchy, always managing to survive and thrive by anticipating the tides of power and aligning himself with the winning side.

Zweig highlights Fouché’s lack of any genuine principles or convictions. He was a man driven solely by the pursuit of power. He began his career as a radical Jacobin, even voting for the execution of Louis XVI. Yet, he later betrayed his former comrades, playing a key role in Thermidor and the downfall of Robespierre. This willingness to sacrifice anyone and anything in the pursuit of self-preservation is a recurring theme in Zweig’s portrayal.

The power Fouché wielded stemmed not from military prowess or charismatic leadership, but from his mastery of surveillance and manipulation. As Minister of Police under various regimes, he created an unparalleled network of spies and informants, gathering information on everyone from the lowliest citizen to the highest-ranking official. This vast network allowed him to anticipate plots, expose conspiracies, and maintain order – or at least the illusion of order – while simultaneously ensuring his own untouchability. Zweig meticulously details the intricacies of Fouché’s intelligence apparatus, revealing the chilling efficiency with which he monitored and controlled the populace.

However, Zweig’s biography is more than just a condemnation of Fouché’s moral failings. It’s a nuanced exploration of the man behind the mask. Zweig acknowledges Fouché’s undeniable brilliance, his strategic genius, and his remarkable ability to navigate the treacherous political landscape of his time. He also hints at a certain weariness and cynicism that characterized Fouché’s later years, a recognition that the endless pursuit of power had ultimately left him empty and isolated.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Zweig’s portrayal is the comparison between Fouché and the “heroic” figures of the Revolution and Napoleonic era. While figures like Robespierre and Napoleon are often idealized as champions of liberty or empire, Zweig suggests that Fouché, in his amoral pragmatism, might be a more accurate representation of the political realities of the time. He was, in essence, the engine that kept the state running, often through methods that were morally questionable but undeniably effective.

Ultimately, Stefan Zweig’s Joseph Fouché is a cautionary tale about the corrupting influence of power and the dangers of unbridled ambition. It’s a reminder that even the most brilliant minds can be seduced by the allure of political expediency and that the pursuit of power can lead to the sacrifice of principle and the erosion of morality. Through his masterful prose and insightful analysis, Zweig offers a chilling glimpse into the heart of a man who was, in his own way, a reflection of the turbulent and often brutal era in which he lived, a serpent lurking in the garden of revolutionary ideals.